Queensland dentists' service in the Australian Army Dental Corps WWII

How did World War II affect Queensland dentists?

D9. Military dental kit. Leather, steel. ADAQ Museum of Dentistry

In 2003, Dr Maurice (Mo) Dingle shared his memories of graduating and starting a dentistry career in war times.

Here's an excerpt of his recollections from handwritten correspondence held in ADAQ's archives (reproduced with some alterations for clarity):

"There would have been three categories of Queensland dentists during the 1939-45 war:

The 'mature' age group, many of whom had already served in the First World War; the younger ones, who volunteered to enlist as dental officers; and

those in the middle, called up for service under the war-time national service regulations.

Most dental graduates of 1940, -41, -42 and -43 enlisted in the RAAF dental branch. Only two Queensland dentists served in the Navy: Surgeon-Lieutenants G. Vincent and A. Ward.

I sat for Senior Exams in November 1939, started dentistry in March 1940, with four other students.

By the time we did our final exams in late January 1944, Medicine and Dentistry were controlled by a Commonwealth Government body called ‘Medical and Dental Manpower Directorate’: the Deans and the Presidents of the Medical and Dental Associations were members of this Committee, which was tasked to decide where new graduates would be allocated. I was one of the three graduates of 1944 who were called up for service in the Army Dental Corps.

There were three Jewish dentists from Germany who graduated with us to become registered. They were already in their forties, they mostly kept to themselves.

Recruit dental examination during World War 2. John Oxley State Library of Queensland

A group of ADAQ members, mostly WW1 veterans, started a voluntary roster to treat recruits.

Many had enlisted because they had been out of work for most of the 1930s. Public dentistry was almost non-existent. The state of their teeth was deplorable.

These ADAQ members brought their own equipment such as extraction forceps and syringes to do urgent treatment at the Exhibition Grounds or Woolloongabba Cricket Ground, which had been taken over by the Army. Preventive dentistry was unheard of in these situations, lots of teeth were charted for extraction. My father was one of those rostered dentists.

I encountered the same rampant caries problems as my father, when I was a dental officer in Kure, Japan, serving with the Commonwealth Occupation Forces in 1946-47, specially with the newly recruited youths.

Major Eric Earnshaw, an older dentist, oversaw dental units in camps around Queensland. Earnshaw recalls being awaken early on Sunday morning in Goondiwindi Recruit training camp, by the camp padre. The dentist’s professional assistance was needed to recover the man’s full dentures: they were inside a glass of water that had frozen overnight in his tent!

Some Queensland dentists served in the Middle East, in places like Tobruk, and were subjected to continuous dive-bombing attacks by German and Italian aircraft.

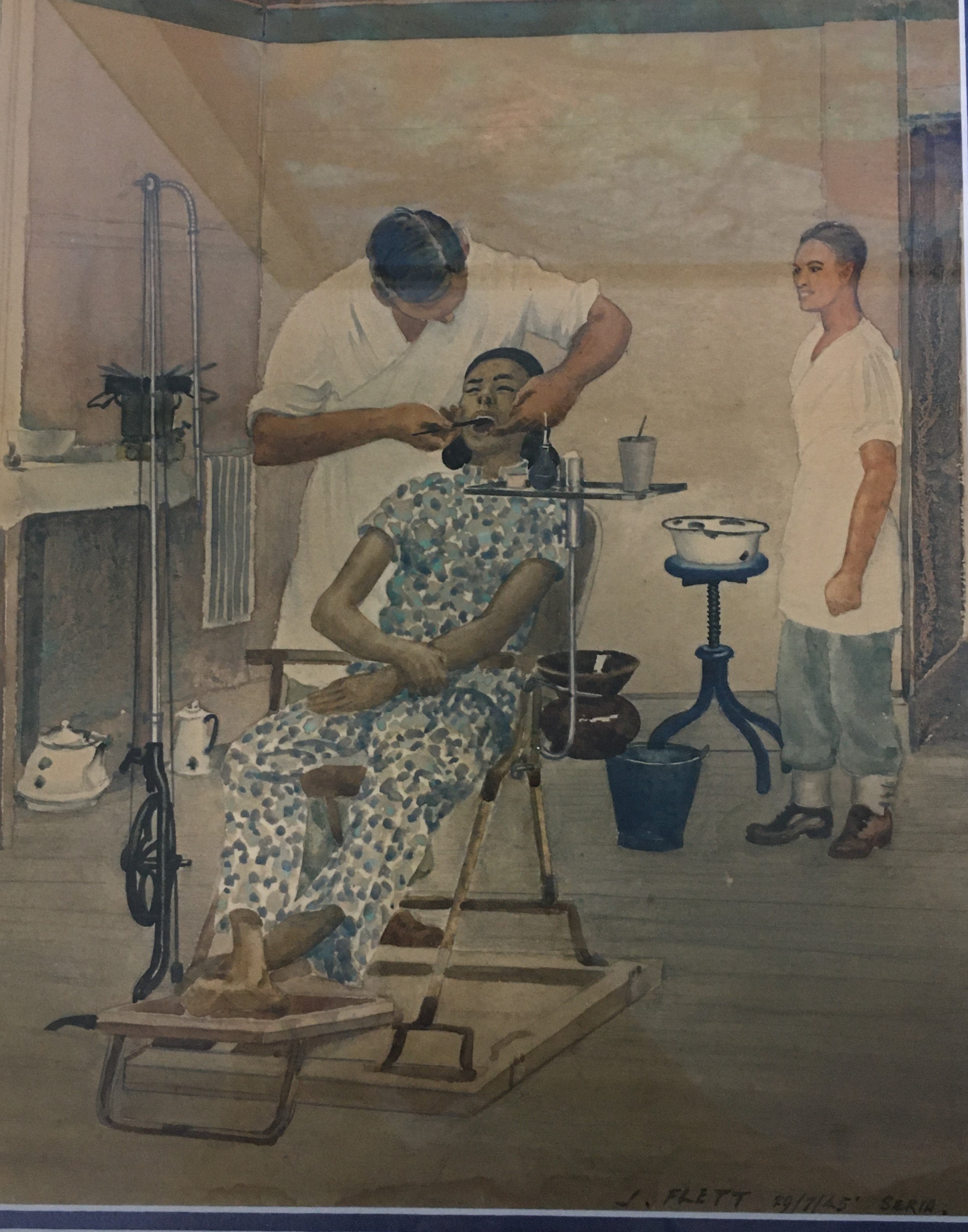

J. Flett, drawing. Dentist and Malay girl, Seria Brunei, 1945. ADAQ Museum of Dentistry. Flett was commissioned as official war artist: see James Flett | Australian War Memorial (awm.gov.au)

D65. Dr Yajima's surgical set. WWII. ADAQ Museum of Dentistry.

For example, Major Jock Clarke MBE spent 7 months in Tobruk as a dental officer. His unit was then sent to Java in February 1942: they spent the next 3 ½ years as prisoners of war (POW) of the Japanese, in Singapore, Malaya and the Burma-Thailand railway.

On his return to Brisbane, Major Clarke bought Mr Owen Pearn’s practice in the AMP Building in Queen St. When he renewed his registration at the Queensland Dental Board, he was told he was recorded as ‘dead while POW’!

Quite a few dentists went to Singapore with the 8th Australian Division. They were all taken POW.

Green dentures were good camouflage...

Not many Army dental officers had access to dental equipment or electricity. Only base units and some hospitals had electric units in their surgeries: most field dental units had to use foot engines in the operating tent, with the mechanics using foot treadle polishing machines.

Primus stoves provided the heat source for hot water sterilisers and for vulcanisers in the lab. Metho lamps were used for waxing up dentures.

Casting inlays was done using a blow-lamp and a casting bucket made from a chisel handle, a length of chain and a jam tin.

Many of the dental units in New Guinea had problems with rust and mould on equipment and stores, especially if they had been involved in a beach landing from a landing barge.

One of the worst materials was the local anaesthetic. It consisted of small tablets of Novocaine, made by Parke-Davis. The tablets had to be dissolved in a small metal cup with Ringer’s solution, by holding the wire handle of the cup over a small methylated spirit burner. These tablets deteriorated under tropical conditions: it was almost impossible to obtain adequate anaesthesia using this stuff.

The usual denture material was vulcanite. Acrylic material was in short supply and was to be used for special cases only. However, rubber was also in short supply. A Brisbane company was granted a licence to make denture rubber to supply the Services.

On processing this material, the resulting dentures often turned out a green colour.

The Diggers reckoned these dentures would be good camouflage if you stood and watched Japanese aircraft with your mouth open…

I think Queensland dentists coped with the interruption to their professional careers well. Many of them rendered sterling service to the Australian Dental Association in the years to follow.

Dr Mo Dingle, March 2003.

From correspondence with Dr Harry Akers, retired dentist and member of the Dental History Preservation Committee.